Enhanced Corporate Governance Requires Proactive Strategy

Good corporate governance requires that boards and senior management of all organizations (including public, private and not-for-profit organizations) be kept fully informed of all material enterprise risks.[1] Unfortunately, recent financial disasters and scandals at major organizations indicate that this is not uniformly true.

In fact, boards of directors, trustees and senior management of the organizations mentioned in this article have received very unpleasant and embarrassing business surprises, even though the underlying risks were known by others in the organization.[2]

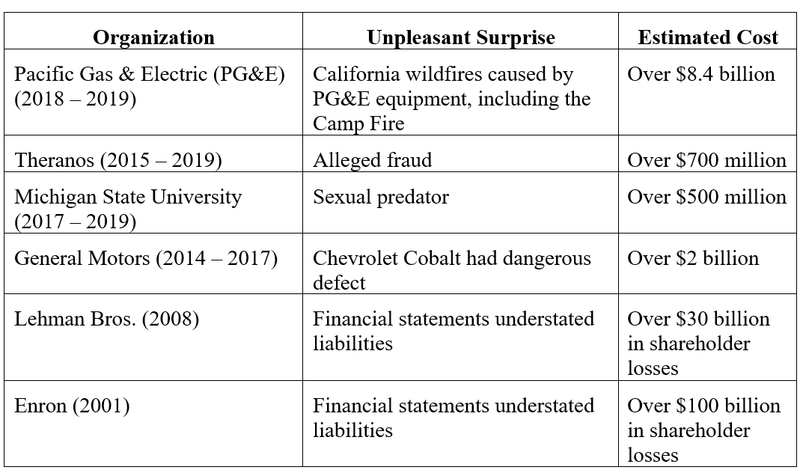

The following is a partial list of financial disasters that happened since the year 2000, demonstrating how even the most diligent and sophisticated boards and management can have unpleasant surprises. This was true even though other employees in the organizations knew or should have known of the problem, including the following organizations:

In each case, the boards of directors and trustees were unpleasantly surprised despite the fact that they had likely complied with all prevailing corporate governance standards. Although there was no independent counsel report for either Pacific Gas & Electric Corp. or Michigan State University to verify what their respective boards knew or did in advance of the unpleasant surprise, subsequent calls for shake-ups in each board make it clear that each board was blamed for the subsequent financial disaster. In the case of PG&E, currently in bankruptcy, one half of the board is expected to be replaced.

Based on an independent counsel report, the board of directors of General Motors Co. scrupulously complied with all prevailing corporate governance requirements before the Chevrolet Cobalt disaster, but nevertheless had no warning that a disaster was coming. The board was blamelessly misled by the assurances of internal safety personnel. General Motors has subsequently reinvented itself so as to avoid repeating the mistakes of the past.

Michigan State University also made certain changes to its processes that will hopefully prevent repetition of its mistakes. Theranos Inc., Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. and Enron Corp. are no longer in business.

Each of these organizations illustrate the importance of a proactive corporate governance strategy by boards of directors and trustees and senior management. Each of these boards overrelied on internal risk and control personnel with virtually no independent checking.

The problem is that what is currently considered good corporate governance practices have been proven ineffective to prevent disasters. In particular, overreliance on internal watchdogs and independent auditors is the main problem. These current practices must be supplemented by independent verification as discussed in this article.

Check the Box

Some organizations have adopted a check-the-box mentality toward corporate governance. They believe that if all the boxes are checked, management and the board have done their job. The boxes include the following:

- Do we have an internal auditor and a compliance officer? Check.

- Do we have reports from the internal auditor and the compliance officer and have we asked questions about the reports? Check.

- Do we have each employee sign a compliance policy? Check.

- Do we have a Sarbanes-Oxley Act hotline? Check.

- Has someone reviewed the Sarbanes-Oxley Act hotline complaints? Check.

- Do we have a prioritized list of enterprise risk? Check.

- Do we send an annual CEO memorandum to employees emphasizing the need for an ethical, law-abiding culture? Check. Etc.

A check-the-box list cannot produce effective corporate governance unless one of the boxes is independent verification. “Trust but verify,” a slogan attributed to President Ronald Reagan, should be the model for CEOs and boards. Verification requires active independent testing and rejects relying solely on the word of internal watchdogs, such as the internal auditor and compliance officer.

Independent Auditors

Some CEOs and boards believe that their independent auditors are capable of identifying significant enterprise risks, and will so advise them. Nothing can be further from the truth. Even the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board agrees. The PCAOB has stated that “an audit made in accordance with PCAOB auditing standards provides no assurance that illegal acts will be detected or that any contingent liabilities that may result will be disclosed.”[3]

It is not the function of independent auditors to identify enterprise risks unless the auditor is informed by the client of the illegal act ,or “there is evidence of a government agency investigation or enforcement proceeding in the records, documents or other information normally inspected in audit of financial statements.”[4]

Of course it is possible for an auditor to be specifically employed to identify enterprise risks. However, this is rare. Even when they are so employed, their opinions are often so chocked full of qualifications and limitations that they are of little value.

Procedures used by the independent auditor for the purpose of forming an opinion on the financial statements may bring possible illegal acts to the auditor’s attention. Such procedures include reading minutes, and inquires of the client’s management, legal counsel and audit committee.

However, the overwhelming majority of independent auditors never detect enterprise risks, and rely upon management representations. The PCAOB specifically sanctions such reliance in the following statement:

The auditor also obtains written representations from management concerning the absence of violations or possible violations of laws or regulations whose effects should be considered for disclosure in the financial statements or as a basis for recording a loss contingency. (See AS 2085, Management Representations.) The auditor need perform no further procedures in this area absent specific information concerning possible illegal acts.[5]

Proactive Steps

Below is a list of proactive best practices which can be engaged in by directors and senior management, some of which have only nominal cost. Directors and senior management may delegate these best practices to other completely independent parties, but they do need to supervise them.

The list below, which is not exhaustive, is arranged in the order of magnitude of the expense of these proactive practices that would be incurred by the organization, starting with the least expensive proactive measures.

Nominal Cost

- Form a risk committee of the board, or specifically assign risk responsibilities to an existing committee.

- Test your ethics line or hotline by making an anonymous call to report some alleged, but fictitious, significant enterprise risk, and then determine whether the information is reported back to both the risk committee of the board and senior management.

- Have dinner with a former employee who voluntarily quit the company. Current employees, fearing retaliation, may not be truthful,[6] and employees who were fired may have a personal agenda based on their involuntary termination.

Moderate Cost

- Employ an independent firm to test the employee culture through surveys and permit anonymous responses. Questions could include, among others, whether an employee would report unethical or illegal activity or enterprise risk to both senior management and risk committee of the board or only to their supervisor or through the employee hotline or otherwise.

- Make certain that at least one board member is reading all whistleblower reports and determining that any reports that appear legitimate are independently investigated.

- Employ an independent firm to survey all supervisors on an anonymous basis to determine whether they would immediately report employee complaints of unethical or illegal activity or enterprise risk to both senior management and risk committee of the board.

Expensive

- Periodically have independent counsel review selective risk topics such as safety issues, compliance with the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, risk issues recently reported by other industry members, etc.

“Enhanced Corporate Governance Requires Proactive Strategy,” by Frederick D. Lipman was published in Law360 on October 22, 2019. Reprinted with permission.

A more detailed discussion of the issues presented in this article are available in Frederick Lipman’s published book, Enhanced Corporate Governance: Avoiding Unpleasant Surprises (Daniel Publishing LLC, 2019).

[1] Lawrence D. Brown and Marcus L. Caylor, “Corporate Governance and Firm Performance,” Georgia State University, Dec.7, 2004, http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=586423. “Is There a Corporate Governance Stock Valuation Impact?”, Rival.com, April 26, 2016, https://rivel.com/is-there-a-corporate-governance-stock-price-valuation-impact/.

[2] Many disasters occur when no one in the organization has actual knowledge of the underlying risks because of faulty enterprise risk analysis, including potential “Black Swans.” For an excellent book on improving enterprise risk analysis see: Hubbard, “The Failure of Risk Management: Why It’s Broken and How to Fix It.” (John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2009)

[3] https://pcaobus.org/Standards/Auditing/Pages/AS2405.aspx.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] See the story of “Pug” Winokur, an Enron director, who tried but was unsuccessful in obtaining information from an Enron risk manager. Redmond and Crisafulli, Comebacks, p. 104.