Federal Circuit Provides Guidance on How Design Patent Claims Should Be Construed: Words Are Limiting and Should Not Be Ignored

According to a recent decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, the words of a U.S. design patent claim can limit the scope of the claimed design, and should not be ignored in the claim construction process. The decision should make it easier to procure and defend a design patent claim of effectively broad scope, but may complicate design patent infringement actions and examination proceedings where the precise meaning of claim language is disputed.

Curver Luxembourg, SARL v. Home Expressions Inc., No. 2018-2214 (Fed. Cir. Sept. 12, 2019), a design patent infringement action, resolved what appears to be a case of first impression in the Federal Circuit, and may be of interest to those who practice design patent law (infringement litigation and design patent procurement). In the past, although there has been some uncertainty in the law, the actual words of the claim of a U.S. design patent have been treated mainly as a formality, with little to no effect on the scope of the patent—claim scope has been determined by focusing on what is shown in the design patent drawings. Curver Luxembourg represents a shift away from that approach. According to the court, “claim language,” not just the drawings, “limits the scope of the claimed design.” Id. slip op. at 2 (emphasis added). According to the court, “it is inappropriate to ignore” the text of a design patent. Id. at 11.

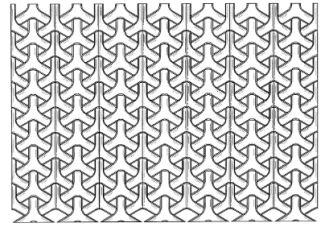

In Curver Luxembourg, the drawings of the design patent-in-suit showed a pattern of overlapping Y-shaped elements. See Figure 1. The patent claim referred to an “ornamental design for a pattern for a chair.” The title of the patent correspondingly referred to a “pattern for a chair.” The drawings, however, did not show a chair. They only showed the pattern of Y-shaped elements.

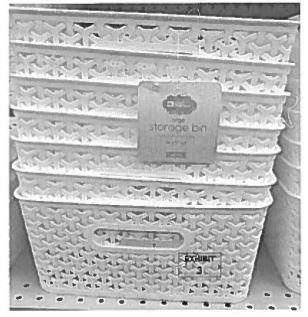

The defendant, Home Expressions, marketed baskets (plastic storage bins with handle openings) that incorporated a pattern of overlapping Y-shaped elements that was similar to the pattern shown in the drawings of the Curver Luxembourg patent. Id. at 4. See Figure 2.

Curver Luxembourg sued Home Expressions for design patent infringement, alleging that the baskets infringed the patent. The plaintiff-patentee argued that the scope of its patent should be determined by focusing on the patent drawings, which are not limited to a chair (the drawings do not show a chair at all, only the Y-shaped pattern). According to the patentee, it was improper to rely on the word “chair” in the claim language (“pattern for a chair”) to determine the enforceable scope of the patent. The Federal Circuit disagreed with the patentee, and affirmed the district court’s dismissal of the complaint for failing to set forth a plausible claim of infringement. The Federal Circuit determined that the design patent was not infringed by the defendant’s baskets. Basically, the court construed the patent claim as being directed to “an ornamental design for a pattern of a chair,” not a “pattern for a chair,” which can be applied to other articles.

Seems simple, right? But the courts and commentators have been struggling for a long time with this issue of whether the text of a design patent claim should have any meaning at all in determining the scope of the claimed design. To reach its conclusion in Curver Luxembourg, the Federal Circuit had to find that certain statements in In re Glavas, 230 F.2d 447 (C.C.P.A. 1956), were “dictum and thus not binding,” Curver Luxembourg, slip op. at 12, or no longer good law in view of Egyptian Goddess, Inc. v. Swisa, Inc., 543 F.3d 665 (Fed. Cir. 2008). (Although the decisions of the Court of Customs and Patent Appeals are binding on three-judge panels of the Federal Circuit, Egyptian Goddess was decided by the Federal Circuit en banc.)

Curver Luxembourg diverges from the Federal Circuit’s non-precedential case of Vigil v. Walt Disney Co., Nos. 99-1310, -1413, 2000 U.S. App. LEXIS 6231 (Fed. Cir. Apr. 5, 2000). In Vigil, the patent-in-suit was directed to a duck call while the accused product was a key chain. See Vigil v. Walt Disney Co., No. C-97-4147, 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22853 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 1, 1998) (trial court opinion, describing design patent-in-suit and accused product). The Federal Circuit reversed the trial court’s imposition of sanctions against the patentee, finding that the defendant’s key chain was not so “remote” from the patented design as to make the action “frivolous.” Implicit in the non-precedential decision is that the Federal Circuit was at least open to the idea that the words of a design patent claim are not important in establishing claim scope—it was not frivolous to suggest that a key chain could infringe a claim to a design for a duck call.

Impact

The direct effect of the Curver Luxembourg decision was to limit the scope of the patent-in-suit so that it was not infringed by the defendant’s baskets. Interestingly, however, the greater practical effect of the decision may be to make it easier to procure and defend design patent claims of broader meaningful scope. The scope of a design patent claim should be the same whether one is defending the novelty of the claimed design over the prior art or asserting the claim against an accused product. As is often said, that which defeats novelty if earlier in time, infringes if later in time. Thus, it should now be possible, for example, to claim only a small portion of a cell phone, and thereby establish an effectively broad claim for the cell phone, without worrying about whether the claim is anticipated by the exact same configuration in a wooden spatula, a box of matches, or some other unrelated device. Although it would still be necessary to establish the non-obviousness of the design, the case as a whole should be an easier carry for the applicant or patentee.

Moreover, as Professor Dennis Crouch was quick to point out, sometimes folks turn baskets over and sit on them. See Federal Circuit Rejects Patenting Designs “in the Abstract.” In Curver Luxembourg, it seems to have been conceded that the Home Expressions baskets were not a chair. But we can expect closer cases where it will be more difficult to determine whether the accused product meets the textual identification recited in a claim. What if the defendant had made a three-legged stool, or an ottoman? Are those products chairs? Sometimes a design feature has aesthetic applicability across a variety of articles. Indeed, the patentee in Curver Luxembourg originally aspired to obtain design patent protection applicable to all furniture, before amending the claim to refer to just chairs. Curver Luxembourg, slip op. at 3. Going forward, will a design for a portion of an “automobile,” for example, be infringed (or anticipated) by the same design in a golf cart, or a riding lawn mower? Is a riding lawn mower an “automobile”? In utility patent infringement cases and utility patent application examinations, a great deal of time is spent determining the meaning of the words of claims. In the wake of Curver Luxembourg, complicated claim-construction arguments based on the words of a design patent claim, not just the patent drawings, may become more common, and practitioners should be prepared to make and respond to such arguments.

© 2019 Blank Rome LLP. All rights reserved. Please contact Blank Rome for permission to reprint. Notice: The purpose of this update is to identify select developments that may be of interest to readers. The information contained herein is abridged and summarized from various sources, the accuracy and completeness of which cannot be assured. This update should not be construed as legal advice or opinion, and is not a substitute for the advice of counsel.