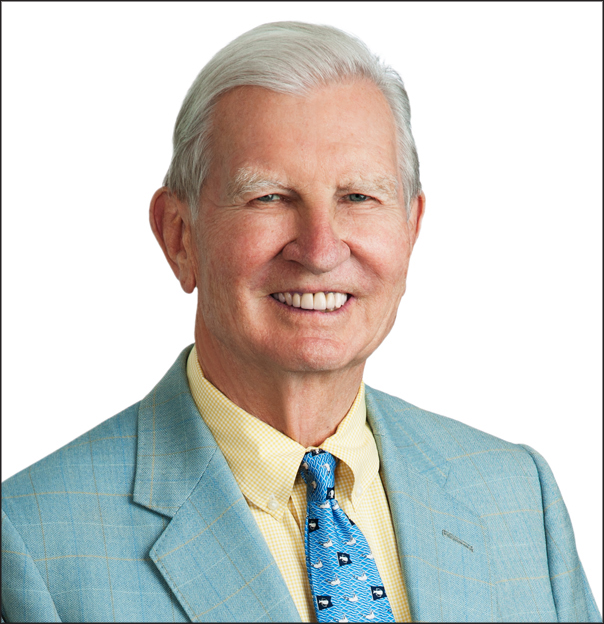

In Memoriam: Joseph D. Tydings

Joseph D. Tydings, a Maryland lawyer and “Kennedy man” who followed his adoptive father’s footsteps into the U.S. Senate, died Monday of cancer in Washington surrounded by family. He was 90.

Joseph D. Tydings, a Maryland lawyer and “Kennedy man” who followed his adoptive father’s footsteps into the U.S. Senate, died Monday of cancer in Washington surrounded by family. He was 90.

Devoted to the state until the end, he took his last breath while cloaked in a blanket bearing the name of his alma mater, the University of Maryland, according to his daughter, Mary Tydings.

Sen. Tydings’ political career in the state was marked by a willingness to take on members of his own Democratic party, often to their annoyance.

“His progressive battles cost him his Senate seat in 1970, but his display of political courage was an inspiration to me and many others,” said Sen. Chris Van Hollen. “In these difficult times, he serves as a powerful example of the best in public service.”

Gov. Larry Hogan praised Sen. Tydings’ record of prosecutions against public corruption and ordered flags to fly at half-staff on the day of his interment. “Sen. Tydings and his family have made a lasting mark on Maryland,” he said.

Born in Asheville, N.C., on May 4, 1928, to Eleanor Davies and Tom Cheesborough, he and his sister, Eleanor, were later adopted by U.S. Senator Millard Tydings of Maryland after his mother divorced his biological father.

“He grew up on a farm in Havre de Grace, Md., and Millard Tydings was a huge influence on his life,” Mary Tydings said. The house where he grew up on the banks of the Chesapeake Bay now belongs to Ashley Addiction Treatment.

He grew up amid privilege — his grandfather married Marjorie Merriweather Post, and Sen. Tydings made childhood visits to her opulent homes in New York City and elsewhere. But he remained frugal throughout his life and didn’t consider himself an elite. “He was a man of the people despite how he grew up,” Ms. Tydings said.

As a youth, Mr. Tydings attended public school in Aberdeen before entering McDonogh School in Baltimore County as a military cadet. Upon graduation, he enlisted in the U.S. Army, and served in one of the Army’s last horse platoons during the postwar occupation of Germany.

A lifelong horse lover, he later would introduce the Horse Protection Act into the Senate, meant to combat the abusive practice of “soring” horses to affect their gait. He was given an award by the U.S. Humane Society for his work.

After completing his service in the Army, Sen. Tydings entered the University of Maryland, where he played lacrosse and football and earned his law degree in 1953.

His political career began in the 1950s, when he served as president of the Maryland Young Democrats. As its president, he once confronted an Ocean City hotel owner who refused to allow black attendees to stay there.

In 1954, he was elected to represent Harford County in the Maryland House of Delegates. There, he fought for greater oversight of savings and loan companies after a major scandal within the industry.

"I was appalled no one was doing anything about it," he wrote in his autobiography, “My Life in Progressive Politics: Against the Grain,” co-written by former Baltimore Sun reporter John W. Frece. The reason, he argued, was that many top politicians in the state were profiting from these schemes.

Later, as a federal prosecutor in the state, he brought several cases against corrupt politicians, including Congressman Thomas Johnson and House Speaker A. Gordon Boone, both who served time in prison.

According to his autobiography, Sen. Tydings brought so many cases against Democratic politicians that, according to his autobiography, U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy once called him and exclaimed: "My God, Joe, can't you ever find a Republican to indict?"

In 1963, at the urging of President John F. Kennedy, Sen. Tydings launched his bid for the U.S. Senate. Kennedy was assassinated on the same November day that Sen. Tydings held his farewell luncheon with colleagues to prepare for his run.

During his single six-year term in the Senate (1965-1971), he championed liberal causes including gun control, civil rights and opposing the war in Vietnam. His advocacy for gun safety also incurred the wrath of the National Rifle Association, which helped defeat him in his re-election bid, according to a biography provided by his family. He also became an enemy of President Nixon after helping to defeat two of the president’s Supreme Court nominees, Clement F. Haynsworth Jr., and G. Harrold Carswell, according to the biography.

After losing re-election, he remained active in political circles, and lobbied in favor of laws to protect the Chesapeake Bay. A favorite hobby was log canoeing on the Chesapeake Bay, which he enjoyed until his later years.

He went on to serve as a member and as chairman of the Board of Regents of the University of Maryland.

At an age when his peers were considering retirement, Sen. Tydings worked as an attorney with Washington law firm Blank Rome LLP.

“He didn’t need to be here for the last 20 years of his life,” said Jim Kelly, chairman of Blank Rome’s Washington office. But Sen. Tydings chose to continue to work toward causes he deemed important.

“It sounds a little trite, but he really was committed to basic notions of justice and fairness,” Kelly said. “He was not afraid to wear that on his sleeve, and he was not afraid to stand up and be counted.”

In 1955, Sen. Tydings married Virginia Reynolds Campbell of Lewes, Del. They had four children and divorced in 1974. The following year, he married Terry Lynn Huntingdon of Mount Shasta, Calif., with whom he had his fifth child. That marriage and two subsequent marriages ended in divorce.

One of Sen. Tydings’ political slogans was “Joe Tydings doesn’t duck the tough ones,” remembered his daughter, and it remained an apt phrase for him until the end of his life. Sick with cancer, he fought off his illness to show up to his oldest grandchild’s wedding on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in September.

In addition to Ms. Tydings, he is survived by his sister, Eleanor Tydings Russell of Monkton; by his children, Millard Tydings of Skillman, N.J., Emlen Tydings Gaudino of Palm Beach, Australia, Eleanor Tydings Gollob of McLean, Va., and by Alexandra Tydings Luzzatto of Washington; as well as by nine grandchildren.

—By Christina Tkacik, The Baltimore Sun